James MacKessack-Leitch, Policy Officer, looks at what Scotland can learn from international experience of land use in our latest blog.

At the Scottish Land Commission Conference, Scotland’s Land and Economy, I spoke about some of the international research we’ve done over the past couple of years looking at various land reform issues, and how other countries organise systems of land use, management, and ownership.

My aim was to get the audience – and now you – to think about some of these big issues, and pose some challenging questions about what Scotland can learn and where we should be going on our land reform journey.

There are three elements that shape our relationship with land regardless of country or jurisdiction: use, management, and ownership. Each has its own distinct features and role to play, but all three are intimately linked.

However, looking outwith Scotland, it quickly becomes clear how different patterns of land use, management, and ownership can be. As everyone is doing it differently, there’s no such thing as normal – or perhaps even radical – land reform; it’s a matter of perspective.

Across the breadth of our international research there are three key themes that consistently arise where there is the greatest difference with the Scottish context: governance (ownership) structures; local governance; and land use and planning. From these areas we have, perhaps, the most to learn.

In Scotland there is a tendency to think of land and property ownership as either private, public, or community – and treat each one differently. Elsewhere, however, there are a range of governance models that exist demonstrating a broad spectrum of ownership models that don’t fit neatly into any of these descriptions. Hybrid governance and ownership models are quite common outside of Scotland, and act to bring various parties together in decision making around land use and management – and crucially give them each a stake in the rights and responsibilities. This hybrid approach also tends to increase transparency and accountability in decision making.

Similarly, where a landowner in Scotland would normally expect to own all the rights to resources attached to the land, elsewhere the separation of usage rights and rights to resources is common. This allows multiple parties to benefit from the full scope of what the land can offer, implicitly recognising that it is the ownership of resources, rather than title, and fostering governance arrangements that are more inclusive and productive.

With regard to local governance, unlike in Scotland, the presence of municipalities of a much smaller scale – both in population and geographic terms – is ubiquitous. These local government structures play a key role in local land use, management, and often ownership, and are empowered with tools from taxation to planning to take a leading role in all local land matters.

For a wide range of land reform objectives it is clear that the presence of these types of local governance structures makes achieving change that much easier – which is perhaps somewhat at odds with the prevailing top-down approach in Scotland.

The final common theme is around land use and planning. The vast majority of countries explored take a zoned approach to planning, and will regularly have much more detailed – and often legally enforceable – land use plans.

This allows much greater clarity around development and ensures that the benefits of development are more widely spread. More in-depth land use planning also provides greater clarity for landowners, decision makers, and the public, and can act as an agreed expression of the public interest in land in the local area.

Taking all that on board, there are then three big questions we need to answer.

Firstly, is there a local governance gap? The role of empowered municipalities across the breadth of the research is clear. As it stands, Scotland doesn’t really have a direct equivalent, or any compensating mechanisms. Taking this question a step further, across the country we see pressure on landowners to engage and take responsibility for inclusive decision making. At the same time landowners of all types are often working to provide public goods as diverse as infrastructure and affordable housing to environmental protection. Is this gap being filled by landowners? Should it?

Secondly, is the Land Use Strategy the missing link? Clear land use planning (and a zoned approach) are prerequisites for many land reform objectives, but are useful tools in their own right. How do we make sure we’re making the right decisions, increase clarity for landowners and the public, and improve decision making?

Finally, what should be normal for Scotland?

Interventions to Manage Land Markets and Limit Ownership [bit.ly/2EoGwxp]

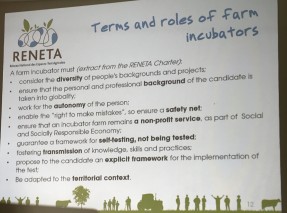

Increasing the Availability of Farmland for New Entrants to Agriculture [bit.ly/2oFZEVp]

Land Value Tax Policy Options for Scotland [bit.ly/2Enit6b]

Local authority land acquisition in Germany and the Netherlands: are there lessons for Scotland? [https://bit.ly/2Abizdo]

The Range, Nature and Applicability of Funding Models to Support Community Land Ownership [bit.ly/2Eu5Y7g]

Review of International Experience of Community, Communal and Municipal Ownership of Land (not yet published)

o land for those who want to farm and reduce barriers to new entrants.

o land for those who want to farm and reduce barriers to new entrants.

a

a

icy challenges including climate action, productivity, and a fair economy. Reforms to both land ownership and use are needed to unlock opportunities for inclusive growth and to make the most of our land for common good.

icy challenges including climate action, productivity, and a fair economy. Reforms to both land ownership and use are needed to unlock opportunities for inclusive growth and to make the most of our land for common good.

wed by a Q&A session.

wed by a Q&A session.

challenges faced in urban areas when it comes to getting involved in decisions made about land and considered how we could better understand the specific challenges and identify opportunities for practical change.

challenges faced in urban areas when it comes to getting involved in decisions made about land and considered how we could better understand the specific challenges and identify opportunities for practical change.