Our Policy Officer James MacKessack-Leitch shares his experience of visiting farm incubators in France and draws parallels for the Scottish sector:

At the end of October I joined a NEWBIE delegation on a trip to northern France to learn more about farm incubators. This is part of the Scottish Land Commission’s work to help increase access t o land for those who want to farm and reduce barriers to new entrants. NEWBIE is a European-funded initiative with the goal of increasing innovation, entrepreneurship, and resilience in the European farming sector.

o land for those who want to farm and reduce barriers to new entrants. NEWBIE is a European-funded initiative with the goal of increasing innovation, entrepreneurship, and resilience in the European farming sector.

France, like Scotland, has an ageing farming population so it is looking for ways to encourage new entrants into agriculture and one of the ways they are doing this is through farm incubators. We are looking at farm incubators as a potential route to increase access to land for agriculture, and they also featured as an option to investigate in our report into Increasing the Availability of Farmland for New Entrants to Agriculture in Scotland, published in May 2018.

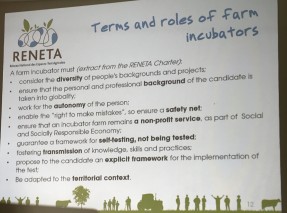

Our hosts for the exchange visit were the French RENETA network, who bring together a range of organisations across the country, collectively supporting around 50 operational incubators units, with over a dozen more in development. Farm incubators are still a relatively new innovation – the first having been established in 2007 – and RENETA itself only formed in 2012, but the demand for, and success of, the model is clearly driving growth.

For RENETA, a farm incubator is defined as a coordinated system offering the conditions necessary to implement a trial farming period, with the provision of:

- A legal framework to enable each candidate to carry out their farm business in autonomy

- Productions facilities – land, as well as buildings and fixed equipment, potentially some machinery and tools

- A multifaceted support and mentoring system adapted to the needs of each candidate.

There was a lot to learn from the trip and it’s worth acknowledging that the French approach to agriculture is very different to ours on a cultural and political level: it’s clear that that approach is the core foundation supporting the activities of the public authorities, the third sector, and farm businesses.

This is perhaps best demonstrated through the actions of the Lille Metropole (MEL) – our first stop on the exchange. MEL is a group of 90 Communes (Local Authorities) centred around Lille and working together to address common issues. Recognising agriculture as a major asset for the development of the local economy, MEL has invested almost €3 million on one 35ha site to provide farmland and fixed equipment for early career farmers: although not an incubator itself, it is a destination for new entrants who have come through the incubators and are seeking to grow their business.

The public sector is being proactive in ensuring that early career farmers have a rung on the ladder after incubation, and that they are willing to make substantial investment to do so.

This proactive approach was also shared at our next stop, with Douaisis Agglo (CAD) – a smaller group of 35 communes – who also provide funding and other support to local agriculture projects. One example was acquiring land to add to existing public land to create a viable agricultural unit, installing a new entrant tenant, providing a €12,000 grant to get the business up and running, and assisting with marketing and access to networks.

Another example was of a municipal incubator providing additional, indirect, support to a new entrant involved in horticulture by ensuring that the local primary school was one of the main customers – demonstrating the power of joined-up public procurement, as well as realising the benefits of a short supply chain.

In all cases, while the public sector often takes the leading role, they work closely with a wide range of partner organisations, across the public sector, private interests, and charitable bodies. Strikingly, it appears quite normal to have multiple partners actively involved and working effectively together in single projects: at a regional level it may involve 60 or more organisations collaborating, agreeing, and acting on a strategic vision for agriculture.

Involving such a large number and breadth of interests in decision making may sound like a recipe for chaos, but in practice the ability and willingness to collaborate is so well-established, and the recognition that everyone is aiming towards common goals is so accepted, it means that getting round the table (admittedly a very big table), agreeing a course of action and then acting on it is reasonably straightforward.

Of course, much of the ability of local government to play a leading and proactive role in supporting agriculture relies on the fact that it has the powers, finance, and personnel to do so – for which there is no Scottish parallel, and no short-term likelihood of change.

There are lessons that are eminently transferrable. The willingness of the public sector to take a leadership role, facilitate discussion and action need not be not resource-intensive, nor requires significant changes to policy or legislation.

Likewise the commitment to collaborate is something the wider agriculture sector here could learn from – if we’re all genuinely acting in the interests of the industry as a whole, then we all share the same ultimate goals. It’s hard to emphasise this enough, but seeing the willingness to collaborate first-hand makes it clear why French agriculture is sustainable and resilient. The creation of farm incubators, giving a start to new entrants, and then success in retaining that next generation of farmers is a clear demonstration of that commitment to innovation and collaboration.

To hear more about farm incubators and my experience in France, come along to the free NEWBIE seminar at Agriscot on 20 November: https://agriscot.co.uk/newbie-farming-incubators-at-agriscot/

a

a

icy challenges including climate action, productivity, and a fair economy. Reforms to both land ownership and use are needed to unlock opportunities for inclusive growth and to make the most of our land for common good.

icy challenges including climate action, productivity, and a fair economy. Reforms to both land ownership and use are needed to unlock opportunities for inclusive growth and to make the most of our land for common good.